This is one of Disney’s most un-Hollywood like films.

Part of that is specifically the shift to culturally relevant stories and storytelling (and yes, another part is the very open representation for people of color that has, for lack of a better word, been missing) with community as a pillar.

But another big part of why Encanto is un-Hollywood is because of its story and how it is told.

In the next 69-part essay I will further explain how Encanto made the magic happen.

[it really isn’t 69 parts but I can assure you it will be just as satisfying as that number.]

But if you’d rather listen to me and a friend go off our rockers in podcast form:

The Generational Family

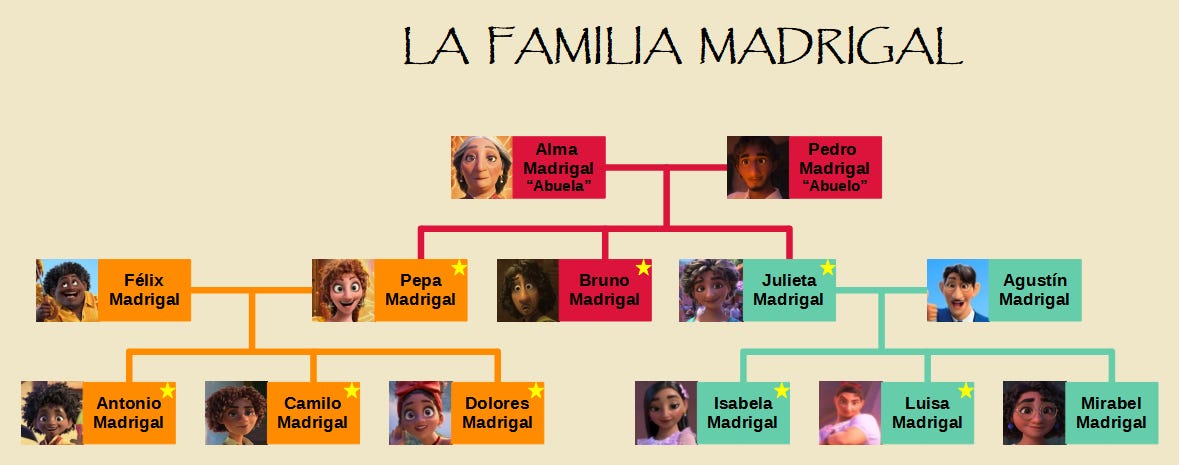

Encanto is about a multigenerational family. I’m sorry if that’s a spoiler or if you haven’t yet seen…a trailer.

We have Abuela spearheading the family tree followed by a package of triplets with powers and then their ensuing offspring (except for Bruno. My boi Bruno only has rats for company *sad beans*).

There’s a great musical number where this entire family sitch is explained along with all their powers, which is absolutely wonderful and fun.

Everyone, save for Mirabel, has a power. They each use it to help better the community and Abuela even mentions in the opening song that they have to use their power to help the community in order to keep the miracle going. Now there’s no scientific backing to that but in the unidentifiable magic that has been granted to their family, whatever works works y’know?

That’s why Mirabel is such a disappointment. Nobody says it outright or makes Mirabel feel lesser for not being granted a power on her birthday, but if she can’t help the community in the amazing, super, powerful way that her family members can, then what’s the point?

Mirabel could’ve easily had this as her villain origin story but I’m really happy that she didn’t.

What she lacks as the squib— sorry, I mean, non-magic person of the family, she makes up for in that big ole’ heart of hers. Mirabel is an unapologetically kind and compassionate human being and that makes us love her.

Mirabel is 100% our flawed protagonist in a colorful cast of unique and entertaining characters. However, this love and affection Mirabel embodies does not come out of a vacuum of her being mistreated or outright abused; she is a product of her community.

There is respect in this family structure. There is an outpouring of love for one another and a fierce desire to protect the whole family, from Abuela to Antonio and his fish, which is unlike the American ideal of a nuclear family that is often portrayed as broken, at each other’s necks, or as perfect as a Bible.

Now the Family Madrigal is not perfect. Not at all, but that is the appearance they want to keep up. Which, I feel, is something a lot of families can relate to in this day and age.

Expectations of Perfection

The Madrigals have their ups and downs in the story but it’s an overall wholesome family dynamic (except maybe when they have that massive BOP against Bruno) but we don’t talk about the cracks in their relationships.

We sing about them.

Luisa and Isabella’s songs are iconic and catchy and absolutely on-point with how each and every character is cracking under the pressure to be perfect and perform at 110% all the time.

Nobody is forcing them to be like this. It is the unspoken expectation of the family Madrigal to be these great benefactors of the community. To give back in a way that only they can and that is taking an emotional toll on the youngest generation.

Their parents did it and now they must continue the legacy and they have no right to complain and it’s not that hard, if we don’t do this who will and and the consequences of their inaction are louder than any action they take—

You’ve heard it once, you’ve heard it a thousand times, but you can never hear an immigration story in the exact same way. Every single person has their own unique perspective on their journeys to wherever they call home, but what Encanto got right is that feeling of THE immigrant and refugee story.

It’s not perfect, and it doesn’t fit every person’s narrative, but it gets across the feelings of a diaspora and surviving and thriving in spite of that. Very specifically, it speaks to a Colombian experience of facing The Violence and finding a way to resolve it without continuing the cycle.

For any second-generation American, our immigrant story usually (but not always) revolves around the idea of a Land of Opportunity and the overwhelming pressure to make our parents’ dreams come true.

That all-consuming fear of disappointing our loved ones, of wasting everything our parents’ sacrificed is a tangible and destructive theme in the movie.

What is the family Madrigal if they cannot provide for their community? If they cannot help, they cannot work, they cannot protect? If they fail to do what they’ve always done?

The dismemberment of Casita and the loss of their powers and, effectively, their identities is the climactic downfall of their perfection, now shattered.

The Matriarchy

This, arguably, is the second most un-Hollywood thing about this movie. There is no epic fight or defeat or loss in the third act to finish out the story. Casita falling apart is one of the most dramatic and action-packed sequences we see.

Instead, there is the silence of mourning. The acceptance of bad actions done for the right reasons. Abuela acknowledging where she went wrong and actually apologizing.

She doesn’t die to absolve her of her sins or to make way for the reign of a next generation. She is Abuela, the matriarch of the family, someone who is loved and respected no matter what.

The women in this story make this ending possible, both behind and on the screen. It is a soft and emotional ending, a catharsis of apology and acceptance and rebirth without any excessive action sequence to tag along.

This love comes back in the form of community as well. Everybody helping each other and lifting one another up in the face of adversity.

Their house was born from a candle sharing light on land their Abuelo died on. That bloodied foundation was uprooted and rebuilt with the love of the multiple generations of the Family Madrigal and the generous hands of the community.

This isn’t just a story of Mirabel ending the cycle of violence her family has been put through.

It is an absolute shattering of it.

And placing love in its stead to finally make this house a home for all.

I found it much more complex that met the eye (oddly, as a lot of these tales are) and I wondered about the use of people’s powers for the community. They serve as kind of a crutch because structures are built around them. From river-routing to healing to horticulture, the Madrigals do it all. There’s power and control, which is Abuela’s way, but it’s also unbearable and no one but Mirabel is able to peel back the layers and learn that the home and the family are truly ready to crack.

And we need to talk about Bruno! When one of the little kids said “I think your power is denial”, I thought, hmm, that sounds like foreshadowing. Abuela is in denial and wanted to see the future as she wanted, not the way it would be. Bruno told the truth people didn’t want to hear and in essence, that rejection of reality comes from Abuela. His character has such a messy story. Wow.