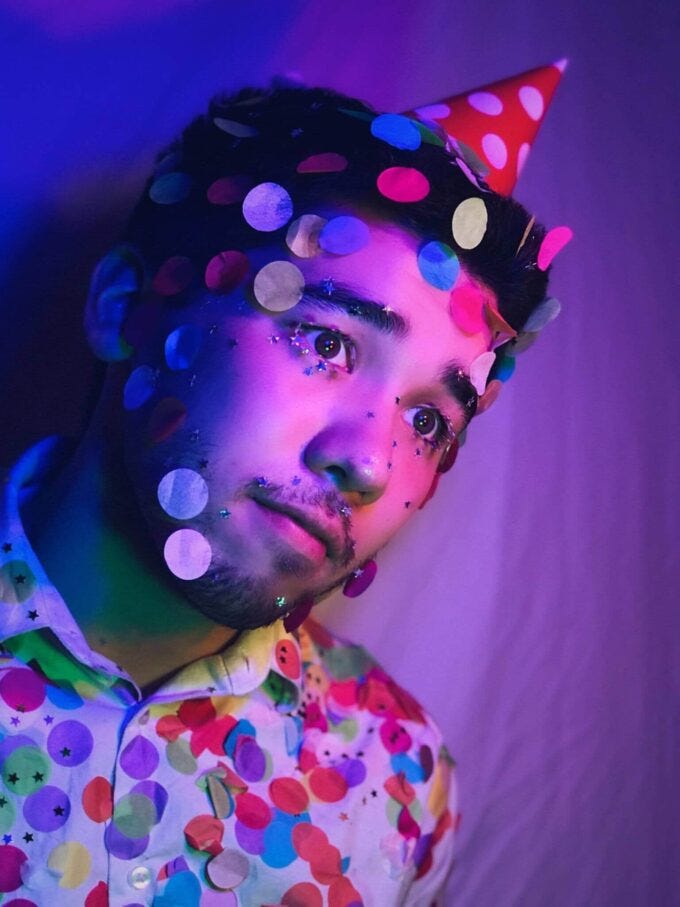

When Preston Choi popped into our Zoom meeting, he had a smile that could light up a room and a calmness that was in direct juxtaposition to the heavy topics he often covers in his plays. Forty-five minutes was not enough to fully delve into the character that is Preston Choi, and while the conversation was never once dry, I was left with more questions than answers, and a burning desire to see what else Choi would do.

There is a quiet confidence about him, something warm and compassionate, which I attribute to his desire to be a teacher, but is equally prevalent in the works he creates. “This is Not a True Story” is one of many Choi has put out, and I had the absolute pleasure to see it performed at the Los Angeles Latino Theater Co. (LATC) earlier this year.

Quirky, melodramatic, spontaneously funny. If the dual theatre masks of comedy and tragedy were personified, they would have to kowtow to this play. We see characters from older and well-established plays like CioCio (Julia Cho) from “Madame Butterfly” and Kim (Zandi De Jesus) from “Miss Saigon” while they pantomime their plays to great comedic effect and existential crises.

And then we get Kumiko/Takako (Rosie Narasaki) from “Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter” rooted in reality but dressed in fiction to sate the age-old story of an Asian woman protagonist who is powerless. It is Kumiko’s abduction from reality and subsequent caricature in a rehashing of her life that pulls apart the purgatory CioCio and Kim find themselves trapped in.

All three women suffer the same fate, over an eternity as their stories are revisited, repeated, re-performed on a myriad of stages. They meet a white man. They give birth. They die. Over and over again to the beat of some sadistic narrator’s drum. Every attempt to avoid their well-established stories leads to the booming voice of some narratorial god admonishing them and cueing them for their next line.

They act demure and subservient and scared. Forced to follow the lines of dialogue written for them by a man enamored with a culture he did not understand. There is fear and then anger and then … acceptance. However they play their role, there will be no changing of the script. But Kumiko is different. Her arrival spells the beginning of the end because she is exactly like CioCio and Kim. She is the most modern retelling of their tragic stories.

And yet she is the product of a truth swaddled in fiction. She is real but she isn’t — a character but a person, an actress but a woman. She is but she isn’t, and that complexity tears the fabric of their very black and white world.

In spite of that, “This is Not a True Story” is a dramatic comedy. In order to accept the comedy, we must accept the tragedy of their original tales. We touch on age-old stories and stereotypes we have seen the Western world place on Asiatic peoples, and we are asked, by way of performance, if we should accept this. If the stories about ourselves should be written by an outsider and used for all of time.

Choi’s answer to this is a hard “No.” He recounts a playwriting class in undergrad and how tired he was of reading the same plays by the same dead white men who had a deathgrip on the media produced. “I wanted to write something for my fellow classmates because why shouldn’t we see ourselves there?”

He mentions how, especially now, with the globalization of media and the popularity of Asian media including “Parasite” by Bong Joon Ho, “it feels like there’s a fascination with Asian identity and class … it feels like there’s this eye on Asian artists and what we’ll put out next.”

Damned if we do, damned if we don’t, a catch-22 of scrutiny that we cannot escape. In response to his own comment, Choi adds that “the dream is to allow mediocre art to survive and thrive. Don’t be afraid to make something mediocre. As an artist, I’m always trying to see what I haven’t seen before on stage — create something new that someone hasn’t quite seen before. A new way of looking at something.”

Create good stuff, create bad stuff, but create. Judge yourself by your own standards because authenticity, as important and varied as it is, cannot define for yourself what you will like.

In order to avoid the deathtrap of having someone else write your story, write your own. We skimmed the topic of authenticity (which is a nuanced and difficult topic to even try to lock down in forty-five minutes), but the shorthand we came up with is that authenticity comes from the heart. It is when you, wherever, whoever you are, makes something that you care about. That makes a story good.

I would definitely consider “This is Not a True Story” some of the good stuff.

We are asked to critically consume this story, Choi’s mixed media background shining through the projection design and tapestry of woven dialogue. As fun as this is, this is not parody, it is satire. He asks us to look beyond just the narrative and continue to ask why. Or why not. To question and critique stories force fed to us by Hollywood. There’s a lot to unpack and beautiful discussion born of this singular work which is equally damning and inspirational in its execution.

These themes of identity and representation season most of Choi’s works.

When asked about his newer works, Choi mentions revision and editing to some things in his pipeline and another performance of “This is Not a True Story” in Chicago. As a final note before we parted ways, Preston left me with this advice: “Be true to yourself. Because I think trying to be true to a wider audience or a larger group is impossible. Please yourself first.”

I couldn’t agree more.

*Originally posted for Asian CineVision on May 24, 2024: https://www.asiancinevision.org/this-is-a-true-story/