Perhaps the most quintessential short story on utopias, with mild, sardonic humor and the brevity of a cup of coffee, Ursula Le Guin’s perfect, envisioned society in Omelas is much less an ideal state of being and much more a transaction.

Short story long: we live in bubbles of utopias already. And Omelas unflinchingly shows us the price we pay for it.

Le Guin begins by talking about the Festival of Summer, a much anticipated event of Omelas, where they celebrate…something. It’s never clear exactly what is being celebrated, but the citizens know it is time to be merry and cheery and they do so with gusto.

Le Guin describes the citizens as “not simple folk…though they are happy” (Omelas 1) and goes on to describe what their utopia is. And to the average reader, it sounds perfect. There is technology. There is a government, some organization, whatever you view as your ideal society, that is what this is.

Le Guin doesn’t want to bog us down with scientific details or how advanced or special this society is, so she leaves the specifics open to interpretation. Our interpretation.

Omelas can be anybody’s world of choice.

Because Omelas already exists. Because Omelas is less a place, and more an ideal.

Omelas is whatever perfect world you can conjure up in your gray matter and Le Guin wants you to think of that fondly and then she wants you to regret having thought about it at all.

Because in as transactional a society is in many capitalist countries, there is a price to pay for happiness.

And in Omelas? The price is so simple, so small, so manageable; it sounds convenient until she describes the broom closet. Until she describes the disgusted ogling. Describes the silence of multitudes that makes the five pages scream.

What is the Cost of a Utopia

In a world of binaries, of haves and have nots, there is that which is good and that which is not. Which in the grand scheme of things is less useful since we’ve come to realize that a lot of what we’ve taken as black-and-white, has tones of gray stretching between the two. In Omelas, and therefore in many utopias by any name, there is a cost to the perfection, sometimes explored, sometimes not, often in relation to the human condition.

For no real discernible reason the price of happiness in Omelas is The Child. Call it tradition, call it a higher power, call it passivity— whatever it is, The Child suffers with no explanation attached to their existence besides the fact that they are. They exist. No one understands why or how this came about, but The Child is what keeps their utopia, a utopia.

With no real words to describe it, The Child is the metaphor, but The Child in this scenario exists and suffers out of respect for how things are done, because according to how things have been and will continue to be, they must continue living life as less to maintain the status quo.

The Child suffers so that the community does not. In order to understand the pleasurable and wonderful lives they are living, each member is allowed to see The Child. They cannot interact with it. They cannot do anything for it.

To do so would be to bring ruin upon the community. There is no scientific backing to this, but it is followed with strict adherence and gospel reverence.

As if all the good the community experiences can only come about with the knowledge of suffering somewhere, of being in a better place in comparison to The Child.

Maybe it gives a greater appreciation to whatever it is the community has. But to hold that knowledge, of The Child quivering, quaking, shivering in pain while you gallivant on the streets and yodel merry joy feels, in itself, like a fake utopia.

The Greater Good

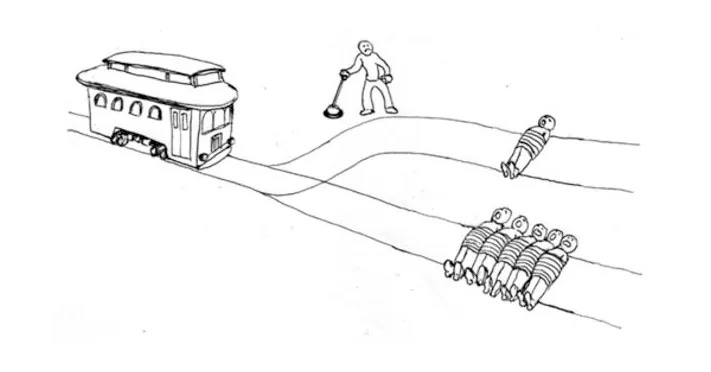

To argue that the suffering of a few in return for the happiness of many calls back to the Trolley Problem.

If everyone is happy at the expense of a few, and in this case, just the one, then that must surely be a worthwhile compromise.

Statistically speaking, yes. It is. The numbers don’t lie and if majority of people are happy, then what of the one person who isn’t, who probably doesn’t even comprehend a life beyond their own suffering?

Emotionally, spiritually, and morally speaking? That’s a…harder nut to crack.

Should you ruin everyone else’s happiness because you feel morally obligated to do something about it?

Can you live with yourself for allowing this blatant disregard for human life continue as you whittle your happy life away above ground?

What choice do you have in a utopia to be angry, sad, or frustrated when the default is happiness?

Are you willing to sacrifice your own sanity and that of The Child’s for the greater good?

When you put it that way, it becomes a question about selflessness and putting your individual needs behind that of the masses.

Choices

And so we arrive at what makes us uniquely human: free will.

Choices.

The ability to think things through and decide for ourselves what we want. Are we granted that in utopias? The choice to be anything else in society? The choice to be different from what is the common norm?

There’s a reason the short story is called “Those Who Walk Away From Omelas.” Because if you cannot fit with what the utopia wants, you must leave. You are of the few, of the forgotten. But you had a singular, individual thought to choose a different destiny.

So while the short story focuses on Omelas as a utopia and the great and grand things it represents, it is named for the people who understand that utopias are not what they seem.

It is named for the people who understand that as easy as it is to accept this utopia as reality, living their truths beyond it is more important.

Omelas and BTS

There’s a million and one ways to slice this short story, and it’s only five fucking pages long. It questions what a utopia is, how they exist, the price of existing, and what that says about the people who thrive in them.

Omelas is a fictional society we are so desperate to achieve, but we must ask ourselves: at what cost?

Those who walk away understand that, and BTS’ “Spring Day” showcases a beautiful music video for what it takes to leave. Also harkening to the Sinking of MV Sewol (April 16, 2014) and paying tribute to almost 300 students who died, the music video introduces Omelas as a seedy motel where the group fucks around in and has some great fun.

It seems to be about the journey in leaving the fabled and distinguished Omelas. Take that as representation for whatever you see fit to our modern society.

The mood gradually shifts until all the members are together, straight-faced and walking away from Omelas.

Or perhaps walking towards something better.

[But they do it together, as many of their music videos have shown them doing. Also a big shout out to Jack Edwards where he made a video and read every book RM from BTS recommended and highlighted the link between “Spring Day” and Le Guin first for me.]

We get moments with each of the members singularly, a pensive face in the crowded room, unsmiling and thoughtful as the joy of the members takes place around them. Almost like each member is struck with the extravagance of their existence and slowly awakens to the reality of it all.

The layers in this music video go beyond just referencing Le Guin and Omelas and the Sewol. There is the visual symbolism of a train and then lyrics to reference Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 thriller “Snowpiercer” (which is built upon layers of social critique as well); the seasons following that of the movie and the metaphorical change in time; abandoned and disused locations that contrast with the members’ colorful existence.

There is the brief thought of BTS entertaining what Omelas is. Only for it to spiral away as they, in some way or another, move away from it.

An empty train. A solitary beach. An abandoned carousel. A pile of clothes. A dimly lit motel room.

Beautifully shot and strung together with the words of a love song.

Yet there are signs of decay in the pastel colors they frolic in front of. There is a darkness they slowly commit to and find the power to escape from as they find a single, barren tree. Its branches devoid of life.

But around its base, the cold, cruel snow melts.

Just like in Bong’s “Snowpiercer.”

Just like in the changing of seasons.

Just like how life goes on.