"Puparia" is Love is and Condemnation for the Medium

Shingo Tamagawa's Critique of the Art Form

I, for once in my life, have no jokes to sugarcoat my words. I love this animation. It’s short, it’s poignant, it’s wholly beautiful in a way that could only be done in the indie scene.

Would it be a little TMI to say that I got literal chills and teared up while watching this? Probably. But it was so unexpectedly good and raw that all I could feel was awe and a selfish appreciation for wanting to create something just as beautiful.

This is art for the literal sake of just creating art and that artist statement is held up to the light in every frame, every motion of the camera and the characters, every hand drawn detail and color penciled shadow. It is bursting with love and attention to detail.

In these 3 minutes, we get a taste of what could be in Japanese animation and it’s cruel in the idea that this cannot, will never be the case for most mainstream media we consume. Because at the end of the day, animation is a product. We consume it voraciously, with no care for how it was sourced or who is laboring behind the screen AND with the expectation that the bottom line will be the most efficient time and money wise.

Shingo Tamagawa is one of the cogs in the machine, yet another animator faced with unreasonable deadlines and the overwhelming desire to create meaningful art in the capitalist creative space. From this feeling of unrest came over a year of soul-searching and the eventual decision to create Puparia for himself, a magnum opus if you will, to showcase his skills as well as to prove just how far the animation medium could be pushed to tell stories.

Tamagawa was fortunate at the time of his disenchantment with the anime industry that he still found a benevolent patron at his parent studio: an eccentric producer at Sunset Studios was more than happy to support his dreams to make an indie short.

A one man band that did every single job in the production pipeline to the best of his abilities and then within a very knowledgeable capacity as a talented artist.

It’s ironic because Tamagawa speaks in this mini documentary by Archipel about this process, how the crowd of people he painstakingly animated by hand is meant to represent the eventual support of a community, but they’ve lost their way and they’re just waiting to have something to believe in again.

He claims the crowd shot at the end is meant to show support. Lying in wait. A muted feeling of appreciation. Tamagawa speaks about wanting the emotion to feel alive on the screen and the nuance is so subtle, almost imperceptible and it is amazing. In a performance space where emotions are often exaggerated and appearances are not to the norm, taking the essence of that human emotion and drawing it by hand to bewitch its audience, with just a hint of movement, is phenomenal. It’s the Mona Lisa in that their expressions are bland enough, but absolutely human enough that you can see the barest hint of reality peeking back at you.

It’s a mirror that reflects the audience. What you feel in the moment will gape at you with wide open eyes. Tamagawa spoke about the Japanese way to show support by showing up and believing. I saw the same images, yet they evoked a dismissive kind of nonchalance. Unforgiving looks. Judgment.

And to each their own, which is the beauty of art well-done: it becomes a collaborative experience between the artist and the viewer and there is a dialogue, though we may never be able to speak to each other about it, we will have experienced it together though only at different times.

As much as the Japanese promotes this community mindset and even though Tamagawa speaks highly of being supported by his community, he still felt the need to undertake this animation behemoth by himself. His hands are dipped in ink in every single screen, his director’s mark indelible. But what a lonely journey he embarked on.

To not trust your vision to others, to feel like you are the only one competent enough, inspired enough, insane enough to create this kind of a vision.

This short is beautiful. And in its layers of symbolism and metaphor we see Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” rear its ugly head, for a brief, shining moment.

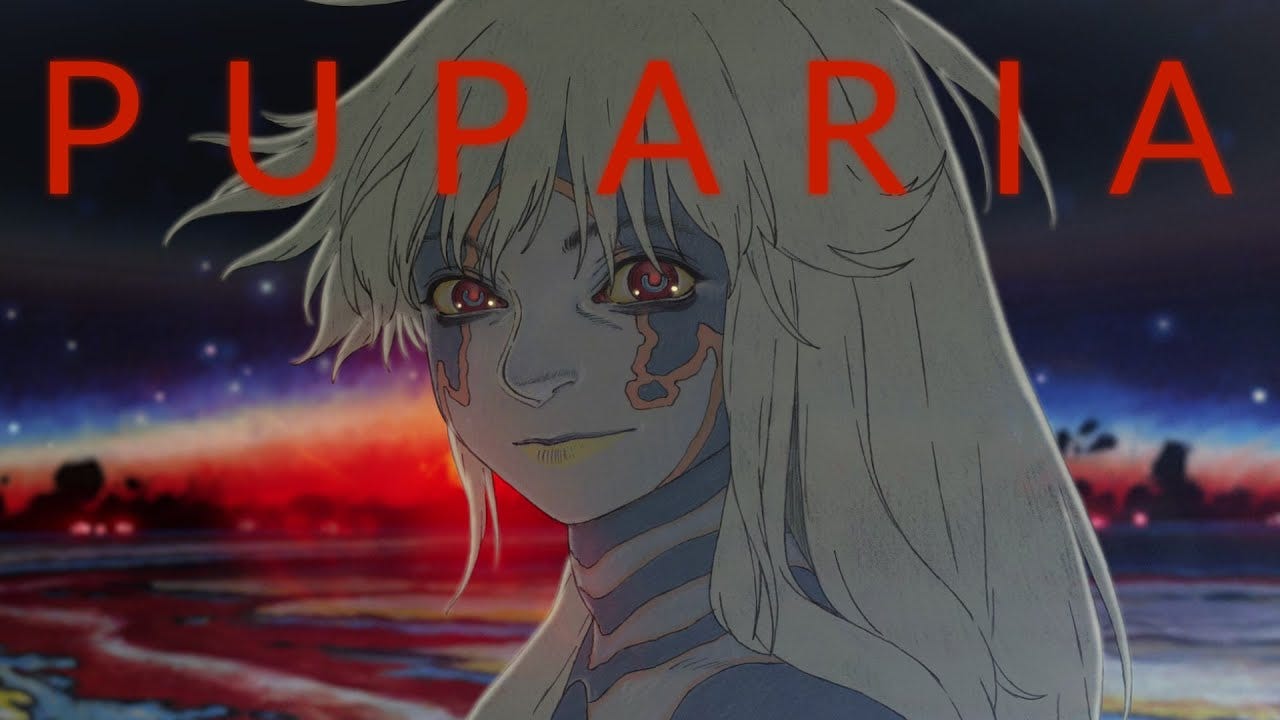

A vermin, insect like creature zooms towards the camera. It looks malevolent. Its eyes bulge and it demands your attention to its disgusting features as much as you desire to pry your eyes elsewhere.

It’s there for a handful of frames, but its symbolism is felt throughout. A loss of identity. The fear of representing yourself. Obligation, expectation, an undeniable urge to continue working, even when our heart is not into the labor.

This is the society we have been inaugurated into, and Tamagawa is disappointed in us. Animation is meant to push the envelope, to make us think and create and do so much more. The fact that we aren’t proves where our loyalties and our motivations lie. He made this work with such tender love and care, and he truly believes this is the kind of animation Japan should be working towards to avoid burnout and to foster this new wave of Japanese art and media in the global world.

And I agree. But like most things in this life

Just because we care, doesn’t mean we will succeed.

If you like this kind of in-depth analysis specifically on animation and even more specifically on the history of animation, I recommend checking out Animation Obsessive, an amazing newsletter that explores the world of animation beyond our Western lens. It’s amazing, it’s phenomenal, I’m waiting for them to write a post on Tamagawa’s Puparia.

While I appreciate the desire to be creatively new and interesting, I don't think it's limited to just someone who doesn't have to worry about money. People can make stuff for economic reasons and be creatively new.